Why is this study being done?

It is widely understood that opioid medications were over-marketed and over-prescribed beginning in the 1990s. As a response, doctors sharply reduced their prescription of these medications. Health systems, pharmaceutical distributors and insurers also pushed for these reductions. While some patients have tolerated this change, others have suffered tragic outcomes, including suicide.

There is no shared understanding of how or why a reduction in opioid medication might lead to suicide. Suicide itself is not typically caused by one bad thing happening. This study will increase our understanding of when changes to opioid prescriptions may be harmful. It will provide the information needed to improve patient care in the future. And crucially, it will sensitize policy leaders to the seriousness of this issue

Why is this important?

The purpose of the CSI:OPIOIDs study is to understand why opioid stoppage might, in some situations, cause or contribute to death by suicide. This information will help health systems, policy makers, and prescribers make better decisions in caring for patients on opioid medication and patients with long-term pain.

My opioid medicines are being stopped right now. Is this study for me?

This study is for people who have lost a loved one to suicide after their opioid medication was stopped or reduced. The research study is not set up to provide clinical support for persons who are experiencing opioid reduction.

However, the study’s principal investigator, posted a detailed guide for patients and family members who are undergoing a dose reduction or discontinuation that they do not want. The Guide is online. It is titled “My doctor says they have to lower my long-term opioid medicine. “What can I do? What do I say?”.

Where is the information for prospective study participants?

Participation in the CSI:OPIOIDs study begins with review of informed consent information and completing a brief screening survey that has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at UAB. Survey responses will be reviewed by a member of the research team. The team contacts potential participants who qualify. Those individuals will then be given the opportunity to consider participating in a longer one-on-one interview and to help obtain access to medical records of the person who died, if possible.

What kinds of things are discussed in an interview?

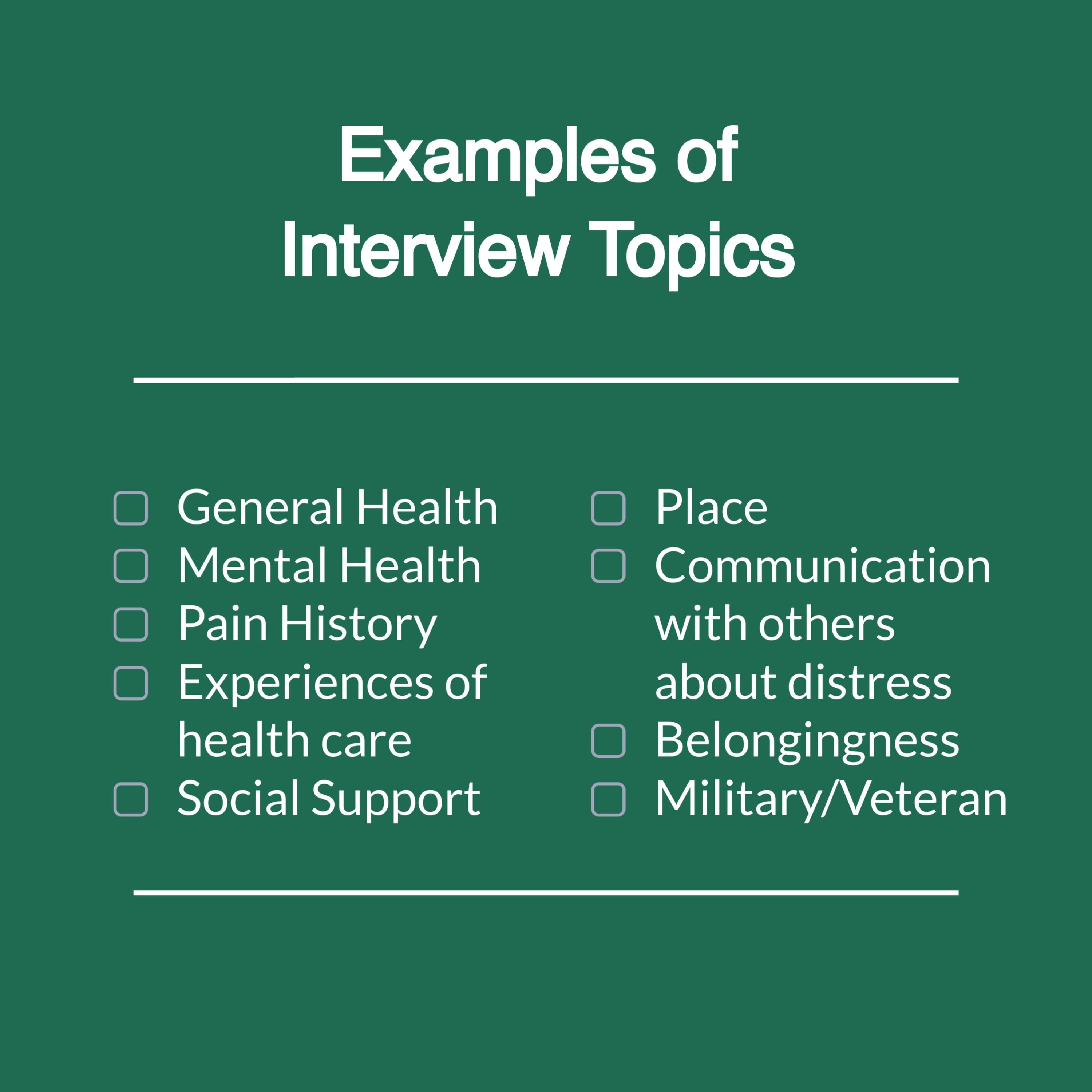

Some of the topics in an interview are shown in the graphic at the right.

It’s important to understand that the interviews are sensitive. People may decide to skip a topic.

Research suggests that when someone decides to be in this kind of interview, they usually regard it as a helpful experience

Can this study lead to change in policies that affect pain patients?

It is our belief that the collective information we glean from studying individual incidents of suicide following opioid dosage modification can and should inform health systems, agencies and professionals who treat patients taking opioid medication.

If a person does not know if opioids were reduced before a suicide, could they be in this kind of study?

For people who were close to someone who died (like a close friend or family member), it is possible to complete the screening survey without knowing for sure what happened to the medication. The first screening question asks “Do you believe that someone close to you died by suicide after a change in pain medication?”

Therefore, if someone believes there was a “change” in the medicine, they could proceed with the screening. Later parts of the survey ask more questions, and permit people to say that they don’t know the details.

Why do a study? Why not just advocate?

Starting in 2016, members of this team saw that patients were being harmed because of changes to prescribed opioids, and often, abandonment. Because the problem was urgent, many of us began with advocacy first, with research beginning in parallel. Examples of advocacy are shown here.

When advocating, members of our team encountered a challenge. Some experts pushed back or expressed doubt about the validity of the concerns expressed. That helped spur us to seek evidence so as to have impact on the medical community and the treatment of patients.

Where can I found out about other studies on reducing prescribed opioids?

People who would like to reduce their prescription opioids should talk to their prescriber. Some, however, may wish to find out about research studies. For people who wish to be in a research study, there are national databases. Usually these databases require a bit of searching, and there may not be a study in your area, but these are places to look.

One option is the online tool Trials Today, which is funded by the United States National Institutes of Health. You can run a search by putting in the name of a health problem (including chronic pain or “opioids”) to learn if trials are happening now.

The National Institutes of Health also have a search engine for their listing of federally funded clinical trials. Their website provides guidance on how to search it, but the search interface is a bit more complex, as it is intended for members of the public, scientists, and other parties.

Will there be future studies of people who may have experienced poor outcomes after opioid reduction but who are still alive?

Right now, the CSI:OPIOIDs study team has chosen to focus on learning the specific accounts related to deaths by suicide. It is a unique type of study. The research team will explore ways to study other harms, or benefits, after opioid reduction after the suicide study is successfully launched.

There has been some research that looks at harms and benefits other than suicide. These studies use large databases and they usually do not have detailed information about each patient’s personal story. Many of them are summarized by Dr. Kertesz online.

Are there any studies that suggest people can benefit after opioids are reduced?

Yes. People are diverse, and so are their pain and medication histories. Reducing prescription opioids appears to be helpful to some people, but harmful to others. It can be hard to know in advance who will benefit. However, some experts report that a benefit is more likely if the reduction involves a collaborative decision, and is done slowly.

One study by our collaborator Beth Darnall, PhD reported on 82 patients who agreed to reduce their doses, starting at doses that averaged 288 milligrams of morphine a day (this was the median) and coming down on average to 150 milligrams. Of these 82 patients, 51 were available for a follow-up evaluation after 4 months. For the group as a whole, the average pain intensity did not increase. It’s important to say that the outcomes differed among people. Many reported a modest reduction in pain or no change in their pain level, even though their dose went down. Others said their pain increased. A small group ultimately required a higher opioid dose, rather than a lower one.

Another study looked at Veterans who had newly started long-term prescription opioids for pain for 90 or more days in a 180-day period. To learn about the outcomes after discontinuing opioids, they measured a combination of outcomes together, which is called a “composite” outcome. The main composite outcome included: accidents causing wounds/injuries, opioid-related accidents/overdoses, alcohol and non-opioid medication-related accidents/overdoses, self-inflicted injuries and violence-related injuries. That particular composite outcome seemed to be lower in those Veterans who had discontinued opioids.

I want to advocate to change policies about pain care. Who do I contact?

We encourage you to think about what forms of advocacy best reflect your values. You may decide to write a letter, share your point of view online, speak to a civic organization or to your faith community. Some members of the team work with the National Pain Advocacy Center.

What agencies monitor the ethics of this research study?

This research study has been approved by two ethical review boards:

- The UAB Institutional Review Board has reviewed and approved public recruitment, the screening survey, and medical records collection for consenting participants

- VA Central Institutional Review Board has reviewed and approved the overall study management, the detailed interview and plans for analysis of data

Are the research study’s data confidential?

Research data are confidential, including the screening survey, interview data and medical record data. Both the Institutional Review Boards for UAB and the VA will only grant ethical approval if stringent data security rules are adhered to. Similarly, personnel who handle data have to undergo repeated training to show that they will adhere to strict privacy rules.

Also, the CSI:OPIOIDs team took additional steps to protect this study from legal demands, such as court orders and subpoenas. To do this we secured two Certificates of Confidentiality, both granted by the National Institutes of Health. One covers all elements of the study governed by the Institutional Review Board at UAB and the other covers all elements of the study governed by the VA Central Institutional Review Board. You can check one of our two certificates of confidentiality here.

How would a person register a concern about this study?

If you are a member of the public and have a question or concern about the study you may choose to write to the study email address at csiopioids@uabmc.edu. The study team will attempt to answer any question it receives. If you believe that your rights have been impeded, limited or violated by the conduct of the study, it is more appropriate to contact one of the Institutional Review Boards listed above.

If you wish to convey a concern or complaint about recruitment supervised by the UAB Institutional Review Board, their contact information is at this link. Their phone number is (205) 934-3789.

If you are a participant and wish to present concerns or complaints regarding the in-depth interviews conducted by our team members, or to the analysis and storage of study data, then the VA Central Institutional Review Board would be the one to contact. Their contact information is at this link. Their toll-free phone number is (877) 254-3130.